Features

Metabolic Health: It’s All About Insulin

Products for metabolic and glycemic health will constitute a huge market segment for decades to come.

By: Sean Moloughney

Carbohydrates are the most important nutrient driving metabolism. Starch (densely packed glucose chains) can cause fast and high spikes of blood glucose if it is rapidly digested in the small intestine, or densely packed energy for the microbiota if it is fermented in the large intestine as “resistant starch.”

Glucose is the primary source of energy for every cell in the body. It is especially important for the brain, which is the most energy-demanding organ in the body due to densely packed neurons (nerve cells). Glucose in the blood is maintained within a narrow range through a powerful hormone called insulin. Thus, carbohydrate metabolism really boils down to glucose and insulin management.

Right now, however, half of all American adults are already diabetic or are insulin resistant (in other words, prediabetic) with increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the next five years. Fortunately, people do not need to wait until they develop diabetes and/or obesity to do something to manage their blood sugar and insulin levels, or to focus on maintaining a healthy metabolism.

The mechanisms of insulin and its role in carbohydrate digestion are not generally well understood (except for most people with diabetes). Here’s a short explanation. As blood glucose is absorbed, the pancreas releases insulin (a powerful hormone) to help transport the sugar into tissues, where it is utilized as energy or stored as fat. The higher the spike in blood glucose, the higher the spike in blood insulin produced to manage it.

Over time, the body can become resistant to the glucose-transporting effects of insulin and require more insulin to effectively manage blood glucose levels within the normal/healthy range (called insulin resistance). It’s as if the cellular lock becomes rusty and the insulin key does not work as well. As the condition worsens, more and more insulin is required to manage blood sugar levels. If the pancreas fails to keep up with the body’s need for insulin, blood glucose levels eventually begin to rise.

Higher levels of insulin cause damage throughout the body’s tissues and promote fat storage. Thus, insulin resistance is the biological connection between obesity and diabetes. This is problematic because higher than normal levels of insulin (called prediabetes) can exist for 10 or 15 years before blood sugar levels finally start to rise. This condition is more common in older adults and in populations at higher risk due to genetics, although younger adults and even children are now being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

Carbohydrate Digestion Over the Past Century

Carbohydrates have been a major component of the diet for thousands of years. The source varied, depending on geography, but corn, potatoes, barley, wheat, tapioca (cassava), and bananas have a long history as food. These foods were not the extruded, puffed, and highly refined breads, cereals, and snacks typical of today’s diets, but were significantly less processed, consumed raw and/or consumed hours after they were cooked.

A significant portion of carbohydrates from these foods used to reach the large intestine. Starch that resists digestion in the small intestine and reaches the large intestine is called resistant starch.

Traditionally, the starch was protected by the food structures, the proteins or fats contained within the whole food, or the starch was retrograded and not glycemic or easily digestible. Today’s food processing strips most if not all of this protective matrix away from the starch, making the carbohydrates high glycemic and more easily digestible. This shift in carbohydrate digestion is contributing to the loss of blood sugar control and compromises a healthy metabolism by overworking and damaging insulin pathways.

A metabolic health (glycemic management) category of foods will be a substantial, consumer-driven force in the coming decades. This category of foods will be larger than the low-fat category, the gluten-free category, and the clean-label category because the underlying need is so tremendous. This category already includes resistant starch-containing foods and supplements, low-carbohydrate foods, and lower glycemic foods. All of these approaches have been successful in peer-reviewed clinical studies in reversing insulin resistance, reversing prediabetes, and helping to restore metabolic and glycemic health.

For food producers of carbohydrate-rich foods, resistant starch is a powerful tool because it promotes metabolic health and glycemic management without requiring people to give up the carbohydrate-rich foods they enjoy.

People are discovering that low-carbohydrate diets help them lose weight and better manage their blood glucose levels, even though they may not be generally aware of the underlying insulin resistance driving their condition. Their success in finally losing weight and gaining control of their health by not eating refined carbohydrates cannot be denied. At the same time, major public health efforts are underway around the world to raise awareness of prediabetes. These two major forces are driving development of the category of glycemic and metabolic health foods and supplements.

Improving Insulin Resistance Without Limiting Carb-Rich Foods

Resistant starch has been defined as starch that resists digestion; it does not digest into glucose in the small intestine but reaches the large intestine where it is fermented by the intestinal bacteria (the microbiome).

The fermentation of natural sources of resistant starch produces more of the short-chain fatty acid butyrate than other fibers tested. Butyrate is the preferred food for colonocytes and has been shown to have strong anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and metabolic health benefits. The fermentation of resistant starch promotes healthy digestion, helps to keep the intestinal barrier intact, and changes the expression of more than 200 genes in the large intestine (an excellent example of “nutrigenomics”). Some of these genes work within the intestinal tract (i.e., triggering intestinal peristalsis, maintaining an intact intestinal barrier, protecting the colon and kidneys from carcinogenic and damaging effects of high protein diets, etc.), but others significantly improve metabolism—they reduce hunger, reduce systemic inflammation, and improve insulin sensitivity within hours.

A century ago, people around the world consumed 30-40 grams of resistant starch/day from their foods (Lockyer 2017). Today, however, American adults typically consume only 2-6 grams of resistant starch/day (Patterson, 2020; Murphy, JADA 2008). Resistant starch has been the largest source of prebiotic fibers in the diet, and as the resistant starch content declined, the microbiota in our large intestine have dramatically shifted. Adding resistant starch back into our diets significantly improves the microbial balance within the large intestine and shifts the microbes back to carbohydrate-digesting types and away from pathogens, (Martinez, 2010; Bendiks 2020).

Numerous clinical trials have shown that natural types of resistant starch significantly reverse insulin resistance and help to reverse prediabetes (without weight loss or exercise). In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a qualified health claim (Docket Number FDA-2015-Q-2352) that resistant corn starch reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes because it reduces insulin resistance (also called improving insulin sensitivity). In recent years, green banana and raw potato sources of resistant starch have also shown improved insulin sensitivity benefits. (See www.ResistantStarchResearch.com for complete references.)

Clinical studies have shown that 15-30 grams of resistant starch/day are needed to reverse insulin resistance in adults with prediabetes. This quantity is very difficult to obtain through food sources alone, as people will not live on a consistent diet of beans, green bananas, and raw oats (the foods with highest levels of resistant starch). Without access to foods naturally high in resistant starch, supplementation is the most effective option for insulin resistant individuals to get sufficient quantities of resistant starch that they need to restore metabolic health.

The improved insulin sensitivity benefit is largest in populations that are highly insulin resistant (but not yet diabetic), but the effect has also been seen in healthy people, overweight and obese adults, prediabetic adults, postmenopausal women, black women, and Asian adults. With improved insulin sensitivity, the malfunctioning rusty locks of insulin resistance are cleaned out and the body is better able to manage blood glucose levels from the entire diet. In other words, people do not need to eliminate carbohydrates from their diet because the insulin is working to maintain healthy blood glucose levels. This is the best option for food manufacturers as people can continue to enjoy bread, snacks, and other carbohydrates while maintaining metabolic health.

Natural resistant starch is available as a dietary supplement. One example is Muniq Life supplement shakes, which deliver 15 grams of natural resistant starch from green bananas and 15 grams of protein. Label claims include “improve gut health,” “promote healthy blood sugar,” “satisfy hunger,” and “prebiotic fiber.” According to Marc Washington, Muniq’s founder, the company is promoting the end benefit of blood sugar control, along with the emotional benefits that resonate with target customers, leveraging the science as the “reason to believe.”

Muniq Life supplement shakes deliver 15 grams of resistant starch from green bananas and 15 grams of protein.

Companies offering carbohydrate-rich foods can replace flour with some types of insoluble natural resistant starch while generally maintaining taste and texture of carbohydrate-rich foods. This delivers the double-benefit of reducing the high glycemic carbs while feeding the microbiota for a boost of insulin sensitivity. For instance, Barilla’s High Fiber White Pasta was made with resistant corn starch. This brand focuses on the fiber content but does not promote any of the metabolic benefits. It cooks, looks, and tastes like regular white pasta while delivering significantly fewer high glycemic carbohydrates and more metabolically beneficially resistant starch.

Barilla’s High Fiber White Pasta is made with resistant corn starch, delivering fewer high glycemic carbohydrates.

Low-Carb & Low Glycemic Diets

Low-carbohydrate diets have evolved and changed since they were first proposed about 200 years ago. A recent example is low “net” (glycemic) foods such as the SOLA Sweet and Buttery Bread. In this bread, the high glycemic refined flour has been replaced with low-glycemic modified resistant wheat starch, inulin and oat fiber. In addition, the bread includes zero-carb, and zero-calorie sweeteners (erythritol and allulose with monk fruit and stevia leaf). Consequently, the glycemic carbohydrate content of one slice of bread is only 2 grams instead of the 7 grams of total carbohydrates in the product.

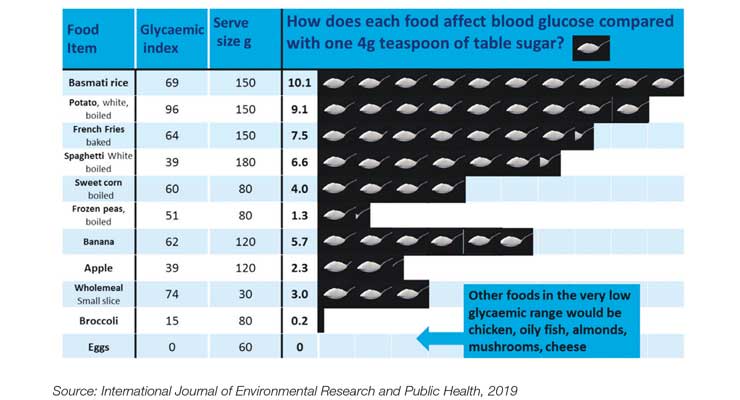

Dr. David Unwin, a general practitioner in the U.K., took another approach. He created consumer-oriented graphics to help his patients select foods that have a lower impact on blood glucose levels (Figure 1). His latest publication, published in 2019 in the International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, reported significant and substantial reductions in blood pressure, significant weight reduction, and marked improvement in lipid profiles (despite a 20% reduction in anti-hypertensive medications), but did not report blood glucose or insulin information. It is only a matter of time before this type of information is more widely available in the U.S. and around the world to help people better manage their metabolic health.

Figure 1. Patient Friendly Infographic to Represent the Glycemic Load of Various Foods

Not all glycemic health developments have been welcomed. A major case occurred in South Africa featuring Dr. Tim Noakes, a respected scientist and co-author of “The Lore of Nutrition,” after he began publicly endorsing a low-carb, high-fat lifestyle in 2012. The backlash from the medical establishment was swift and brutal, resulting in a high-profile court battle. The lawsuit was initially brought by a registered dietitian who complained that Noakes had tweeted to a mother that she should wean her baby onto low-carbohydrate, high-fat foods. After a four-year battle, Noakes was cleared of any misconduct in 2019. He further co-wrote “Real Food on Trial: How the Diet Dictators Tried to Destroy A Top Scientist.” He continues to promote insulin management as the underlying problem driving low carb diets.

Statistics & Cost of Poor Metabolic Health

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported in its 2020 National Diabetes Statistics Report that an estimated 88 million adults aged 18 years or older (about 34.5% of all U.S. adults) had prediabetes in 2018. According to the CDC report, about one-third of U.S. adults have had prediabetes since 2005. The percentage of people actually aware that they had this condition has doubled from 6.5% to 13.3% between 2005-2008 and 2013-2016, due to major educational efforts by the CDC, the American Heart Association, and the American Diabetes Association, among others. These educational campaigns will continue to drive the development of foods for glycemic and metabolic health.

While the personal consequences and constant vigilance of managing blood sugar levels in diabetes are critical, the collective impact of the escalating diabetes epidemic is enormous. Since 2000, The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) has reported that the global prevalence of diabetes in the 20- to 79-year age group has grown from 151 million people to 463 million people (a more than 300% increase in less than 20 years). The IDF is currently estimating continued escalation to 700 million people by 2045, with the U.S. accounting for 48 million people in 2019, projected to increase 33% to 63 million people in 2045 (9th Atlas, Nov. 2019).

It is easy to see how the healthcare costs of managing Type 2 diabetes are significantly higher than staying healthy. In 2007, the estimated national average cost per case was $443 for prediabetes, $2,864 for undiagnosed diabetes, and $9,975 for diagnosed type 2 diabetes (Zhang 2009; Wu, 2017). Major groups, including the IDF, the CDC, the American Heart Association, Diabetes UK, and many more institutions around the world are promoting major campaigns to increase awareness and diagnosis of prediabetes (only 11% are aware they have it), and then advocating for changes in lifestyle, diet, and weight management to reverse the condition and prevent the development of Type 2 diabetes by maintaining healthy blood sugar and insulin levels. This effort has only gained urgency as diabetes has been linked to more serious complications and significantly higher mortality from COVID-19.

SOLA Sweet and Buttery Bread contains low-glycemic modified resistant wheat starch, inulin and oat fiber.

Conclusion

Consumers know that carbohydrates significantly impact their metabolism. They are learning that glycemic management is important through the elimination and/or reduction of refined carbohydrates in their diet. They are willing to take strong actions to lose weight, to prevent diabetes and its lifetime consequences of drugs, cellular damage, and never-ending blood glucose control. There is a tremendous opportunity for the development of foods and supplements that help manage blood glucose, blood insulin, and products that help maintain a healthy metabolism.

Products for metabolic and glycemic health will constitute a huge market segment for decades to come. Resistant starch, low carbohydrate diets, and low glycemic foods are the most validated approaches to meet this need. It is too early to tell how large the low-carb population will become and how severely the food industry will be affected. Food manufacturers should get busy and innovate to serve this strong demand. Sales of carbohydrate-rich foods are at risk of continued stagnation and decline without the development of these types of innovative foods to help consumers manage blood sugar, blood insulin, and metabolic health. Stay tuned to this consumer trend because it’s not going away.

References

- Bendiks ZA, Knudsen KEB, Keenan MJ, Marco, ML. (2020) Conserved and variable responses of the gut microbiome to resistant starch type 2. Nutrition Research. 77: 12-28. Doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.02.009

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

- International Diabetes Federation, ISD Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition.

- Lockyer S, Nugent AP. (2017) Health effects of resistant starch. Nutrition Bulletin. 42(1): 10-41.

- Martinez I, Kim J, Duffy PR, Schlegel VL, Walter J. (2010) Resistant starches type 2 and 4 have differential effects on the composition of the fecal microbiota in human subjects. PLoS One. 5(11): e15046. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015046

- Murphy, MM, Douglass JS, Birkett A. (2008) Resistant starch intakes in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 108(1): 67-78. Doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.012

- Patterson MA, Maiya M, Stewart ML (2020) Resistant starch content in foods commonly consumed in the United States: A Narrative Review. J Acad Nutr Diet 120(2): 230-244. Doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.10.019

- ResistantStarchResearch.com provides complete citations for clinical studies on natural sources of resistant starch as well as explanations on food sources, the FDA health claim on reduced risk of diabetes and proposed mechanisms of action.

- Unwin DJ, Tobin SD, Murray SW, Delon C, Brady AJ. (2019) Substantial and sustained improvements in blood pressure, weight and lipid profiles from a carbohydrate restricted diet: an observational study of insulin resistant patients in primary care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16: 2680. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152680

- Wu J, Ward E, Threatt T, Lu ZK. (2017) Progression to Type 2 diabetes and its effect on health care costs in low-income and insured patients with prediabetes: a retrospective study using medicaid claims data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 23(3): 309-16. Doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.3.309.

- Zhang Y, Dall TM, Chen Y, Baldwin A, Yang W, Mann S, Moore Vm, Le Nestor E, Quick WW. (2009). Medical cost associated with prediabetes. Population Health Management. 12(3): 157-163. Doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.12302.

About the authors: Rhonda Witwer is Executive Director of www.ResistantStarchResearch.com. She previously served as Vice President of Marketing & Business Development at International Agriculture Group. She has a BS in Chemistry from Butler University and an MBA from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. She can be reached at RhondaWitwer@gmail.com. Amy Gilliland is a Food Scientist with more than 15 years of experience in Applications, Product Development, Technical Service, Business Development and B2B Sales in the Food Ingredient sector. She holds a BS in Chemistry, Foods and Nutrition from Rutgers University and an MS in Applied Chemistry from The New Jersey Institute of Technology. She can be reached at amygilliland00@gmail.com.