Columns

Sugar Content Claim Litigation on the Rise

Plaintiffs are monitoring whether a company abides by all relevant FDA regulations, so it’s important to understand requirements and confirm disclaimers.

In the last 15 to 20 years, healthy eating and healthy lifestyles have become mainstays in popular culture. People have become more cognizant of what they’re putting in their bodies, and the amount of sugar in a product can be used as a simple measure to gauge whether to buy a product or not. Consumers depend on companies to tell them truthfully what’s in their products. In turn, there have been a variety of recent lawsuits and settlements concerning sugar content claims on food labeling.

In this article we will explore the different types of sugar content claims, the requirements for making each type of claim on a label, and the basis for these lawsuits with the goal of helping you and your company avoid facing a similar situation.

Nutrient Content Claims Generally

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to regulate food labeling through the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (FPLA). The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA) allows for the use of claims on labels that characterize the level of a nutrient in a food, also known as “nutrient content claims.” Examples include “sugar free,” “high in vitamin C,” “low in saturated fat” as well as comparative claims (e.g., “fewer calories”). Nutrient content claims are authorized by FDA and must comply with very specific FDA regulations as discussed below.

In recent years, there has been a rise in popularity among the use of nutrient content claims in food labeling that are focused on the sugar content of foods, from modifying the types of sugar used in products to making new lines of products without sugar (e.g., “sugar-free” “no added sugar,” and “zero sugar.”

Given the very specific FDA requirements to make such claims, along with the materiality of such claims to consumer purchasing decisions, it comes as no surprise that class action challenges and plaintiff demand letters alleging that such claims are in violation of FDA requirements—or are otherwise false and misleading under state consumer protection laws—have surged. In light of the increased litigation around such claims, we outline here the requirements for sugar related nutrient content claims and describe recent litigation that highlights the pitfalls that can arise in making such claims.

Sugar Content Claims

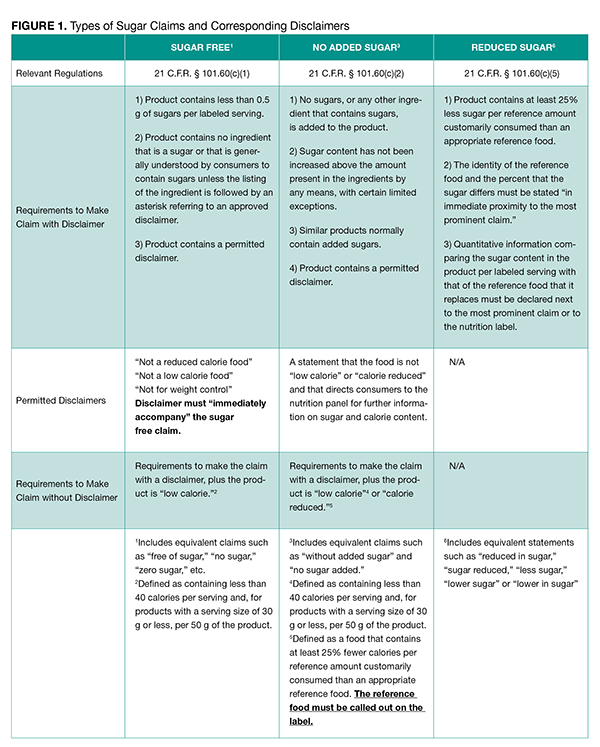

According to FDA regulations, there are three categories of “sugar” content claims for food: sugar free claims, no added sugar claims, and reduced sugar claims. Each claim carries its own requirements, governed by 21 CFR § 101.60(c)(1). These requirements are separate from nutrient content claims for dietary supplements, which are generally governed by 21 CFR § 101.13.

“Sugar free” is a nutrient content claim that includes equivalent claims such as “free of sugar,” “no sugar,” “zero sugar,” etc. [21 CFR § 101.60(c)(1)]. To properly use a sugar free claim on a product, the product must: 1) contain less than 0.5 g of sugar per labeled serving; 2) contain no ingredient that is a sugar or that is generally understood by consumers to contain sugars unless the listing of the ingredient is followed by an asterisk referring to an approved disclaimer; and 3) contain a permitted disclaimer [21 CFR § 101.60(c)(1)]. The disclaimer must “immediately accompany” the sugar free claim and must be one of the following: “not a reduced calorie food,” “not a low calorie food,” or “not for weight control.”

To make a sugar free claim without a disclaimer, the product must adhere to the first two requirements and must be low calorie, defined as containing less than 40 calories per serving and per 50 g of the product (for products with a serving size of 30 g or less). For dietary supplements, “sugar free” claims may be used for vitamins and minerals, but only for those intended for infants and children younger than two years old.

Historically, consumers associate sugar free claims with the idea that a product is also low in calories. To combat that association, FDA mandates that disclaimers must be included on the labeling of products that use “sugar free” claims (but that do not meet the requirements for a low calorie or reduced calorie food) to ensure that consumers receive an accurate depiction of a product’s nutrient information and can make informed food choices for maintaining a healthy diet. Specifically, the sugar free claim must be immediately accompanied, each time it is used, by either the statement “not a reduced calorie food,” “not a low calorie food,” or “not for weight control.”

“No added sugar” claims (also includes “without added sugar” and “no sugar added” claims) mean that the manufacturer did not process the food with any added sugar or sugar-containing ingredients, although the food may nevertheless contain “sugar alcohol” or artificial sweeteners as well as naturally-occurring sugar [21 C.F.R. § 101.60(c)(2)]. The sugar content must not have been increased above the amount present in the ingredients by any means, with certain limited exceptions. Products with no sugar added claims must contain a disclaimer that the food is not “low calorie” or “calorie reduced” (unless the food meets the requirements for a “low” or “reduced calorie” food). The disclaimer, in turn, must direct consumers to the nutrition panel for additional information on sugar and calorie content. Similarly to “sugar free” claims, for dietary supplements, vitamins and minerals may contain a “no added sugar” claim if the intended use is for infants and children less than two years of age.

“Reduced sugar” (also includes “reduced in sugar,” “sugar reduced,” “less sugar,” “lower sugar,” and “lower in sugar”) is a comparative statement that may be used on a food label. The food must contain at least 25% less sugar per reference amount customarily consumed than an appropriate reference food [21 CFR § 101.60(c)(5)]. Reduced sugar claims are different from “free” or “no added” sugar claims because FDA does not require a disclaimer; however, reduced sugar claims must include the reference food on the label. For example, for a beverage, a claim could read “this carbonated beverage has 30% less sugar than the average soda.”

Our team has created a quick reference chart (Figure 1), of the type of sugar claims and their corresponding disclaimers.

Recent Litigation

The FDCA does not give individual consumers a private right of action to bring a claim to enforce the requirements of FDA’s rules or regulations. However, state consumer protection laws often incorporate by reference many provisions of the FDCA, so in certain jurisdictions, consumer class actions against food and dietary supplement companies can be brought under state consumer protection statutes.

In the context of sugar-related claims, such class actions typically claim that a particular sugar-related nutrient content claim is false and/or that its advertising or labeling mislead consumers in violation of state consumer protection laws. These alleged offenses are known as deceptive advertising. These claims frequently occur in California, where the state’s Unfair Competition Law (UCL) and Sherman Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Law (the state food, drug, and cosmetic laws) incorporate many FDA regulations and standards while also giving private consumers a cause of action.

Historically, plaintiff claims under state consumer protection laws have tried to argue that a “sugar free” and similar nutrient content claim made for certain higher calorie/fat products mislead a reasonable consumer to believe that the product is healthy or contains fewer calories than it actually does, and therefore, consumers are deceived by the claim. In such cases, the court has applied an objective standard of whether a reasonable consumer (not necessarily the plaintiff) would likely have been misled under the circumstances, to determine whether a claim is deceptive or not. When applying the “reasonable consumer” test to such cases, the courts have generally found that a reasonable consumer is unlikely to be misled as to the sugar content of a food where the Nutrition Facts panel clearly discloses the sugar content.

For example, in Truxel v. General Mills Sales, Inc., the plaintiffs alleged that the defendant’s health and wellness claims were deceptive because of the amount of added sugar contained in its product. However, the court for the Northern District of California held that no reasonable consumer could be deceived about a product’s sugar content when the product’s label “plainly discloses the amount of sugar in the product, regardless of whether it may or may not be healthy as a result [2019 WL 3940956 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 13, 2019)].

This decision is in line with a previous decision by the same court in Clark v. Perfect Bar, LLC (“a reasonable consumer cannot be misled about a food product’s alleged ‘excessive’ sugar content where that food’s label plainly discloses the sugar content”) [2018 WL 7048788 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 21, 2018)]. The outcomes of these cases were defendant-friendly, in that the court recognized that a reasonable consumer has the ability to take a defendant’s label as a whole to assess its overall impact on health.

In light of such cases, plaintiffs have increasingly shifted their approach in sugar-related nutrient content claims away from deceptive advertising claims subject to the “reasonable consumer” test, and toward technical violations of the FDA’s regulations involving the rules on disclaimers. As mentioned, products labeled “no sugar added” that are not “low” or “reduced calorie” foods must include accompanying warnings disclosing that the product is not “calorie reduced” or “low calorie” [21 C.F.R. § 101.60(c)(1)(iii)]. Because the Sherman Law incorporates FDA regulations, some courts have found that allegations involving FDA regulations are not subject to the reasonable consumer test—a test that had limited success of private plaintiffs in these cases.

For example, in Bruton v. Gerber Products Company, the plaintiffs asserted that Gerber’s “no sugar added” claims violated California’s UCL and Sherman Law because Gerber failed to use a disclosing warning that its products indeed had a high caloric value [703 Fed. Appx. 468, 2017 WL 3016740 *2 (9th Cir. July 17, 2017)]. The Ninth Circuit court held that this violation of FDA disclaimer requirement was not subject to the reasonable consumer test. This meant that the plaintiffs could move forward with their case, when in past instances the claim might have been dismissed. Decisions like this one lowered plaintiffs’ burden for bringing lawsuits related to the sugar nutrient disclaimers.

Essentially, as long as a plaintiff can demonstrate that a product with “sugar” claims did not include its accompanying disclaimer or involved another technical violation of FDA requirements for such claims, the claim is more likely to survive summary judgment under state law regardless of whether a reasonable consumer would have been deceived by the claim.

Many consumer lawsuits settle out of court because of the difficulty in arguing against the lack of a disclaimer on products with clear sugar content claims. For example, Kellogg recently reached a settlement of $20 million in a class action lawsuit where consumers alleged that Kellogg falsely advertised its cereals as healthy and nutritious when the products had high sugar content. For Kellogg, the risk of going to trial outweighed the cost of settling.

While FDA’s requirements for sugar content claims appear strict, the silver lining for the industry is that curing a potential technical violation involving disclaimers is typically straightforward. Additionally, the increase in litigation about these claims has the potential to help the industry and regulators better understand when qualifying language, such as a disclaimer, is necessary and when it can be forgone.

Take the FDA’s reaction to the class action lawsuit against Campbell Soup Company and Pepperidge Farm, Inc. in August 2021 as an example. The consumers alleged that Campbell’s products did not comply with nutrient content claim regulations because their labeling had “0 g Sugars” and “0 g Total Sugars” claims but failed to contain the proper sugar-free disclaimer [National Law Review, Mar. 25, 2022; Vo XII, No. 84]. Clearly, FDA took notice. In January 2022, FDA issued guidance to address frequently asked questions about nutritional facts labeling, and in it, the agency spoke directly to the issue at hand in the Campbell class action.

FDA clarified that additional statements such as disclaimers are not required for quantitative nutrient content claims, even though such quantitative claims are still subject to the general requirements for nutrient content claims. So for example, unlike a “sugar free” product claim, a “0 g total sugars” claim need not be accompanied by a “not a low calorie food” or “not for weight control” disclaimer. FDA guidance on sugar content claims continues to evolve in response to internal decisions by the agency and in reaction to complex litigation questions in need of federal clarification. FDA’s willingness to adapt its position on the use of sugar claims demonstrates that the current litigation can help to mold regulations in a way that benefits both manufacturers and consumers.

Conclusion

Products with sugar claims, like “no added sugar,” “sugar free” and “reduced sugar,” require disclosing statements on labeling. So when planning the next product launch, be vigilant with its regulatory compliance. Litigation over these sugar nutrient content claims is less focused on whether consumers were deceived by advertising. Plaintiffs are now monitoring whether a company abides by all relevant FDA regulations before the product hits the shelf. It is in a company’s best interest to confirm that product labeling contains all its necessary disclaimers. Although litigation provides some federal clarification, good compliance can ensure that these types of cases are not on the horizon.

For more information about recent litigation regarding sugar nutrient content claim, how it may impact your business, and what you can do to help manage your risk, please reach out to Venable’s Food and Drug Law Group.

About the Author: Todd Harrison is partner with Venable, which is located in Washington, D.C. He advises food and drug companies on a variety of FDA and FTC matters, with an emphasis on dietary supplement, functional food, biotech, legislative, adulteration, labeling and advertising issues. He can be reached at 575 7th St. NW, Washington, D.C. 20004, Tel: 202-344-4724; E-mail: taharrison@venable.com.